Chaucer and the Astrolabe

Geoffrey Chaucer was a learned man of the 14th century (c.1340-1400) who was not only author of The Canterbury Tales, but a customs officer, justice of the peace, member of Parliament, possible spy for Richard II, and competent astronomer.[1] He knew both astronomy and the astrolabe.

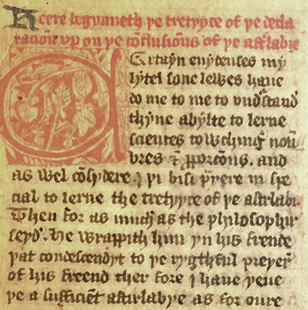

Around 1391 Chaucer began to write a Treatise on the Astrolabe, beginning with the lines: “Little Lewis my son” starting the first technical manual written in English for his son or a close friend describing the theory and operation of the astrolabe:

|

Chaucer Treatise on the Astrolabe manuscript c.1400, Harvard Library |

“Lyte Lowys my sone, I aperceyve wel by certeyne evydences thyn abilite to lerne sciences touching nombres and proporciouns; and as wel considre I thy besy praier in special to lerne the tretys of the Astrelabie. Than for as mochel as a philosofre saith, ‘he wrappith him in his frend, that condescendith to the rightfulle praiers of his frend,’ therfore have I latitude of Oxenforde; upon which, by mediacioun of this litel tretys, I purpose to teche the a certein nombre of conclusions aperteynyng to the same instrument. I seie a certein of conclusions, for thre causes. The first cause is this: truste wel that alle the conclusions that han be founde, or ellys possibly might be founde in so noble an instrument as is an Astrelabie ben unknowe parfitly to eny mortal man in this regioun, as I suppose. An-other cause is this, that sothly in any tretis of the Astrelabie that I have seyn there be somme conclusions that wol not in alle thinges parformen her bihestes; and somme of hem ben to harde to thy tendir age of ten yeer to conceyve.

“This tretis, divided in 5 parties, wol I shewe the under full light reules and naked wordes in Englissh, for Latyn ne canst thou yit but small, my litel sone. But natheles suffise to the these trewe conclusions in Englissh as wel as sufficith to these noble clerkes Grekes these same conclusions in Grek; and to Arabiens in Arabik, and to Jewes in Ebrew, and to the Latyn folk in Latyn; whiche Latyn folk had hem first out of othere dyverse langages, and writen hem in her owne tunge, that is to seyn, in Latyn. And God woot that in alle these langages and in many moo han these conclusions ben suffisantly lerned and taught, and yit by diverse reules; right as diverse pathes leden diverse folk the righte way to Rome. Now wol I preie mekely every discret persone that redith or herith this litel tretys to have my rude endityng for excusid, and my superfluite of wordes, for two causes. The first cause is for that curious endityng and hard sentence is ful hevy at onys for such a child to lerne. And the secunde cause is this, that sothly me semith better to writen unto a child twyes a god sentence, than he forgete it onys.

“And Lowys, yf so be that I shewe the in my light Englissh as trewe conclusions touching this mater, and not oonly as trewe but as many and as subtile conclusiouns, as ben shewid in Latyn in eny commune tretys of the Astrelabie, konne me the more thank. And preie God save the king, that is lord of this langage, and alle that him feith berith and obeieth, everich in his degre, the more and the lasse. But considre wel that I ne usurpe not to have founden this werk of my labour or of myn engyn. I n’am but a lewd compilator of the labour of olde astrologiens, and have it translatid in myn Englissh oonly for thy doctrine. And with this swerd shal I sleen envie.” [1]

Chaucer’s Treatise on the Astrolabe was written in Old English and survives in some 32 manuscripts, second only to the copying of The Canterbury Tales. In 1900 Walter Skeat [2] examined many of these manuscripts and concluded that only seven or eight are “first class” copies of Chaucer’s original text. In fact, many of the scribes were clueless as to what they were copying. All of the manuscripts held today represent copies of Chaucer’s Treatise made after his death. Many of the manuscripts have errors and some are incomplete. However, Chaucer’s text itself is incomplete, as Chaucer himself apparently ended his text rather suddenly in mid-sentence with the last words “howre after howre”.

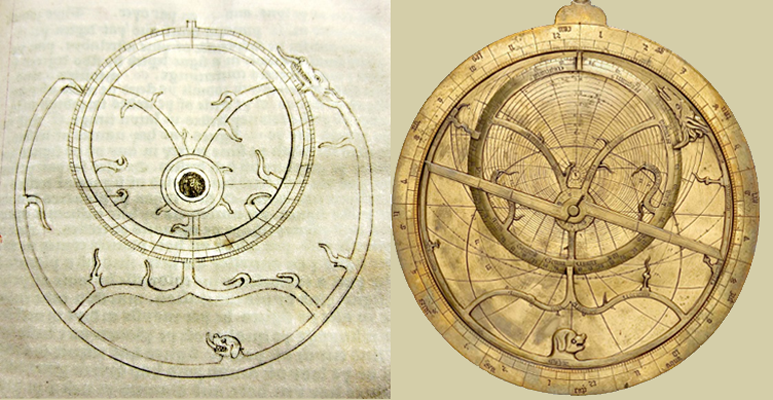

Several of the manuscripts include drawings of the astrolabe that Chaucer describes. None can be shown to come from the hand of Chaucer, but the drawings closely match several existing astrolabes held in collections today. Which one is Chaucer’s? Catherine Eagleton makes a case none of the so called “Chaucer astrolabes” belonged to Chaucer and that “the [astrolabe] instruments were probably made from the diagrams and text of the manuscripts, and suggest that Chaucer’s posthumous fame encouraged the production of astrolabes to his design. It was not so much ‘Chaucer’s own astrolabe’ as ‘an astrolabe just like Chaucer’s’”. [3] One of the finest examples of a “Chaucer Astrolabe” held by the British Museum was made circa 1326, fourteen years before Chaucer’s birth. Another, perhaps contemporaneous astrolabe upon which the NASS astrolabe is modeled, was made around 1370.[4]

NASS is offering a 7-inch (180mm) 3D-Printed version of an Astrolabe in the Tradition of Chaucer tailored to your latitude. Go to: NASS Shop - Sundials & Astrolabes

Chaucer drew upon at least two medieval texts for details of the astrolabe: De Sphaera, written by the mathematician John de Sacro Bosco (died c. 1236) which was claimed at the time the “most popular university text”[5] and Compositio et Operatio Astrolabii that at one time was solely attributed to the Jewish Persian astronomer Mashallah (740-815 CE) of the Abbasid Caliphate in Basra, but now more likely is believed to be a compilation from different authors.[6] Regardless of origin, the text was “most widely known [by learned men] in Chaucer’s time”.[7]

The astrolabe is the story of the stereographic projection, originating with the Greek astronomer Hipparchus (c. 150 BCE), who is credited with discovering the mathematical means of projecting the domed spherical sky onto a flat round plate. “The emergence of the astrolabe as a single instrument began with the bringing together of two forerunners in Greece in the second century BCE: the dioptra – an instrument for sighting the altitudes of celestial bodies – and planispheric [stereographic] projections which could be used to represent the celestial sphere on a flat surface.”[8]

Hipparchus’ star catalog as well as his mathematics was ultimately passed to Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria (c. 100-170 CE) who produced an updated and most famous star catalog the Almagest containing 1022 stars. But the Almagest was really a book on cosmology, mathematics, motions of the planets and the moon, precession of the equinox, and of course, the last major star catalog of antiquity.

Ptolemy’s writings were translated into Arabic, and in fact the word “astrolabe” comes from the Arabic al-Asturlāb, a transliteration of the Greek word ἀστρολάβος astrolabos that was in turn the amalgamation of two Greek words astron "star" and lambanein "to take". Hence astrolabe means “star taking [instrument]”.

Theon of Alexandria wrote “On the Little Astrolabe”, the first Greek text on the astrolabe to make its way to Persia circa 390 CE. But the influence was profound. By 622 CE with the founding of Islam, there was a need for practical astronomy to determine the hours of prayer and to form the Quibla, the direction to Mecca. It permeated society and made its way into the church as well. The painted dome at Qusayr ‘Amrah is the oldest vault of the heavens known:

“The Syriac-speaking community in the region [know as Qusayr ‘Amrah in the Syrian Desert] appears to have had considerable interest in stereographic projection of the skies, as witnessed by the activities of Severns Sebokht (d. 666 CE). Severus Sebokht was the bishop of Qinnasrin, an ancient town that held an important position in the defense system of Syrian fortresses from Antioch to the Euphrates River and was about a day's journey from Aleppo. He not only wrote in Syriac a treatise on constellations, but he composed, also in Syriac, a treatise on the astrolabe compiled from Greek sources.

|

|

“Painted on a domed ceiling in the provincial palace of Qusayr ‘Amrah [is a design of the heavens] … which would be seen looking down on a globe. Though the fresco in the Syrian dome has been damaged over the years, it is evident that it too represents a stereographic projection from the south ecliptic pole of a celestial globe, showing the skies to about 35° south declination.”[9]

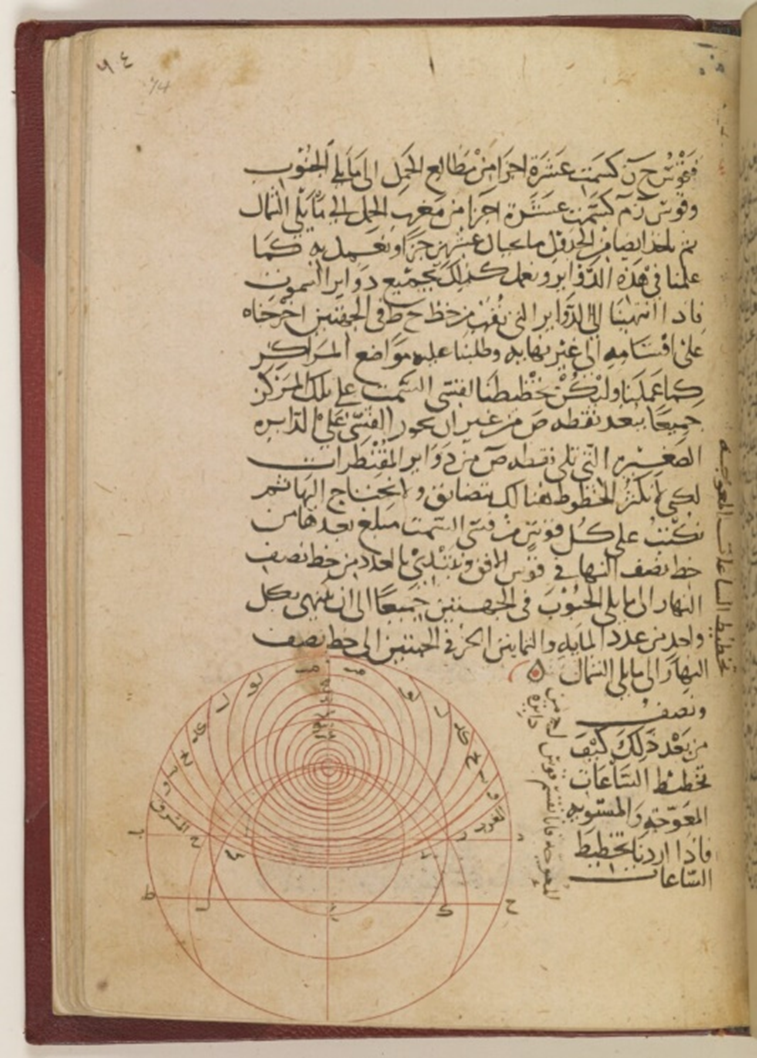

Nearly two centuries before the famous Persian astronomer ibn Aḥmad al-Bīrūnī (973-1048 CE) wrote about astronomy and the astrolabe, Ahmad ibn Muhammad al Farghani (c.820-860 CE) wrote On the Astrolabe, the earliest known Arabic treatise on the astrolabe. Al Farghani clearly showed the stereographic construction of celestial sphere circles projected onto a flat plate and diagramed the construction of the Climate Plate for specific altitudes.

From Persia the astrolabe made its way to Moorish Spain and from there “The astrolabe was almost certainly brought north of the Pyrenees by Gerbert of Aurillac (future Pope as Sylvester II), where it became part of the quadrivium [medieval university curriculum involving the “mathematical arts” of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music] at Reims France sometime before the turn of the 11th century.”

The elegant ornate astrolabes seen in museums today were a medieval status symbol, rarely used by the owner. However, there were court astronomers such as Mashallah that were very adept at using the instrument, particularly for preparing astrological prophecies. But a far simpler astrolabe, the Marine Astrolabe, evolved for navigation and helped establish the age of exploration. Navigators used this astrolabe, like the quadrant that would follow, to measure the altitude of the sun and stars to determine a ship’s latitude.

Al Farghani On the Astrolabe illustrating a Climate Plate. British Library: Oriental Manuscripts, Or 5479, ff 37v-85r, in Qatar Digital Library

Al Farghani On the Astrolabe illustrating a Climate Plate. British Library: Oriental Manuscripts, Or 5479, ff 37v-85r, in Qatar Digital Library