- Details

- Hits: 1279

On October 4, 2025 Madison Historical Society of Ohio was able to have their sundial returned after 32 years, when in 1993 it was moved to the lawn of Lake County Courthouse to reduce the chance of vandalism. The sundial was originally placed at Madison Home 100 years ago on Saturday, October 24, 1925 during a conference of the Women's Relief Society. From 1904 to 1962 the state ran this building as it was run since 1889, for the needy widows, mothers and children of Ohio’s veterans. They named this building the Madison Home.

On October 4, 2025 Madison Historical Society of Ohio was able to have their sundial returned after 32 years, when in 1993 it was moved to the lawn of Lake County Courthouse to reduce the chance of vandalism. The sundial was originally placed at Madison Home 100 years ago on Saturday, October 24, 1925 during a conference of the Women's Relief Society. From 1904 to 1962 the state ran this building as it was run since 1889, for the needy widows, mothers and children of Ohio’s veterans. They named this building the Madison Home.

Cheryl Swackhammer, president of the Madison Historical Society, opened the rededication ceremony and thanked everyone who had made the sundial's move back to Madison possible. The return of the dial was spearheaded by Kenneth Gauntner, a former Madison Township trustee's and Lake County administrator.

The circular bronze dial with open gnomon sits on a tapered pedestal 3ft (1m) high with a bonze plaque on the pedestal recording the dedication for the Women Relief Society 100 years ago.

Read the article by gmcvey in the Gazette On-Line News at https://gazettenews.com/sundial-monument-rededicated-at-madison-historical-society/

- Details

- Hits: 3332

|

Prosciutto di Portici (Ham) Sundial

Photo: Getty Images

|

The Prosciutto di Portici Sundial, more often called the Portici Ham Sundial, dates from the first century somewhere between 8 BCE to 79 CE. This small silvered bronze dial was uncovered on 11 June, 1755 in the ruins of Herculaneum (current day Portici) in the "Villa of the Papyri", buried in volcanic ash and charred papyri from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. The form of the sundial, which resembles a ham, has been extensively studied. It is an altitude dial with similarities to the cylindrical sundial.

Live Science reporter Kristina Killgrove writes, "Historians have long assumed that the owner of the Villa of the Papyri was L. Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, the father-in-law of Julius Caesar." https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/romans/prosciutto-di-portici-a-portable-sundial-that-looks-like-a-pork-leg-and-it-was-likely-owned-by-julius-caesars-father-in-law-before-mount-vesuvius-erupted

Calpurnius likely commissioned the Epicurean philospher Philodemus to drave the numerous charred scrolls at Villa of the Papyri. Killgrove commented that "This may explain why the Roman pocketwatch was shaped like a ham. For adherents of Epicurean thought, the lowly pig was often used as a metaphor, as it was seen as a naturally pleasure-seeking creature.

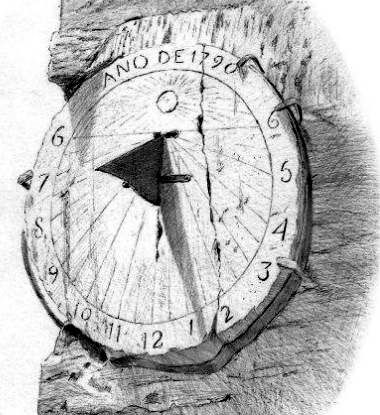

To clarify the use of the dial and the drawn lines attributed in the article as "hours before or after sunset" were actually temporal hours. The lines measuried the hours from sunrise to sunset. Temporary (ancient) hours go across the dial face and vertical lines represent the boundary between the zodiac signs representing the twelve months of the year. In this dial the twelve months have been “folded” and the month pair labeled between the lines: IUN-IU (June-July), MA-AU (May-August), AP-SE (April-September), MA-OC (March-October), FE-NO (February-November) and JA-DE (January-December). Notice that both July and August are used and the longest shadows occuring at the end of June while the shortest occur at the end of December. Further, since July and August are named, the dial was created after the reign of Julius and Augustus Caesar, and in particular when Augustus renamed the month Sextilis to August in 8 BCE.

The Ham dial has a fixed gnomon, the flattened piece at middle-left in the photo. When properly working, the gnomon is actually much longer and the tip set a specific distance above the dial face and at the upper left corner of the hour-date lines. To read the time, the dial is rotated from a string at top of the dial until the shadow falls on the vertical date line (or distance between) corresponding to the date. Like the cylindrical sundial, time is read from the downward shadow of the tip crossing the temporary hour line.

The Ham dial also has “folded” hour lines that run across the dial to tell temporary (ancient) hours. The lines are from top to bottom are for sunrise, 1st/11th, 2nd/10th, 3rd/9th, 4th/8th, 5th/7th, and at bottom, the 6th hour line for mid-day.

- Details

- Hits: 4502

Esteban Martínez Almirón has published a new book Historical Sundials: Forgotten Andalusian Treasures (Relojes de Sol Históricos Tesoros Andaluces Olvidados) In it he reviews over 400 sundials from the Andalucian region of southern Spain Originally to celebrate the 25th year of the website https://relojandalusi.org/

Esteban Martínez Almirón has published a new book Historical Sundials: Forgotten Andalusian Treasures (Relojes de Sol Históricos Tesoros Andaluces Olvidados) In it he reviews over 400 sundials from the Andalucian region of southern Spain Originally to celebrate the 25th year of the website https://relojandalusi.org/

Esteban Martínez Almirón began showing his sundial drawings on the site. Ultimately more than 60 drawings are in his book, and many are posted on the @stbnart Instagram site. He presents the historical sundials using the themes according to geographical location and building type (e.g. on farms or country houses for daily time telling; churches, cathedrals and other sanctuaries; and civil buildings and public places). Unfortunately many dials have been lost to history and no longer exist.

Martínez Almirón looks briefly at portable sundials of Andalusia, particularly in Sierra de Huelva, the city of Ubeda (where its Renaissance sundials stand out) and the dials of the "New Populations" ("Nuevas Poblaciones"). The book is self-published. If you are interested in purchasing a copy, you can visit https://relojandalusi.org/relojes-de-sol-historicos/. The book cost is 12 euros plus shipping. Text in Spanish.

- Details

- Hits: 6358

Dr. Federica Gigante, from Cambridge Univerity's History Faculty, discovered a rare astrolabe sequestered in a museum at Verona, Italy. Publishing in Nuncius (1 March 2024) Dr. Gigante presents "a hitherto unknown remarkable astrolabe from Al-Andalus which likely belonged to the collection of Ludovico Moscardo (1611–1681) assembled in Verona in the seventeenth century. The astrolabe is datable to the eleventh century and features added Hebrew and Latin inscriptions. It underwent many modifications, additions, and adaptations as it changed hands and owners over time thus becoming a palimpsest object. With its added translations from Arabic into Hebrew, the astrolabe closely recalls the recommendations prescribed by the Spanish Jewish polymath Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089–1167) in the earliest surviving treatise on the astrolabe in the Hebrew language written in 1146 precisely in Verona." Today the astrolabe is preserved at the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo.

Dr. Federica Gigante, from Cambridge Univerity's History Faculty, discovered a rare astrolabe sequestered in a museum at Verona, Italy. Publishing in Nuncius (1 March 2024) Dr. Gigante presents "a hitherto unknown remarkable astrolabe from Al-Andalus which likely belonged to the collection of Ludovico Moscardo (1611–1681) assembled in Verona in the seventeenth century. The astrolabe is datable to the eleventh century and features added Hebrew and Latin inscriptions. It underwent many modifications, additions, and adaptations as it changed hands and owners over time thus becoming a palimpsest object. With its added translations from Arabic into Hebrew, the astrolabe closely recalls the recommendations prescribed by the Spanish Jewish polymath Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089–1167) in the earliest surviving treatise on the astrolabe in the Hebrew language written in 1146 precisely in Verona." Today the astrolabe is preserved at the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo.

"This isn't just an incredibly rare object. It's a powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews, and Christians over hundreds of years," said Dr. Gigante.

- Details

- Hits: 7322

Smithsonian Magazine holds a photo-of-the-day contest. Winner on 30 Oct 2023 was Harita Sistu who took a photo of the large sundial of Jantar Mantar, Jaipur India (taken in July 2022). Harita notes: "I wanted to try my best to capture just how massive the instrument is and bring focus into the incredible skill that went into designing and constructing it."

Harita Sistu - Award winning photo of the Equatorial Sundial at Jaipur, India

Harita Sistu - Award winning photo of the Equatorial Sundial at Jaipur, India

- Details

- Hits: 8347

Smithsonian Collection - Pocket sundial by Bourgaud of Nantes, 1660–1675. (MA.325565) Smithsonian Collection - Pocket sundial by Bourgaud of Nantes, 1660–1675. (MA.325565) |

From the National Museum of American History is an article about "How did a French pocket sundial end up buried in a field in Indiana?" published 20 July 2022 by Kidwell & Schechner.

It started in 1860 when Dr. Elisha Cannon, while plowing a field in Indiana, came across a strange object. It was a French Butterfield sundial. It ended up in the Smithsonian collection 100 years later, where it quietly sat until recently when curator Peggy Kidwell wanted to learn more. She contacted Dr. Sara Schechner, David P. Wheatland Curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments at Harvard University, to join the investigation.

The dial is inscribed "Bourgaud Nantes" showing it was from the workshop of a clockmaker in Nantes, France. As with all Butterfield dials it contained a magnetic compass with declination corrections for orienting the dial to north and a miniature plumb bob to hold the dial level. The gnomon support is in the traditional shape of a bird allowing the gnomon itself to be adjusted to a range of latitudes. Look closely at the chapter ring of hour marks in Roman numerals. Outside the numerals is one hour line scale and on the inside of the numerals is a second scale. The user could approximate the time between these two scales, done for the extreme latitudes 30 and 55 degrees.

"In her research on sundials in the American colonies, Schechner has drawn attention to several of these dials, and notes that some 18th-century French sundial makers, like Pierre le Maire (and his son of the same name), made pocket dials that carefully listed the latitude of places of French interest in both North and South America." How did the dial end up in Indiana? It could have been carried there by Dr. Cannon and his wife Gulielma, Quakers who in 1840 left North Carolina, finding that "living in a state where African Americans were legally enslaved was intorable." Or the dial may have been left a century earlier when the French occupied much of what is now Indiana, leaving outposts such as Terre Haute and possibly a lost sundial.

Read the article: https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/pocket-sundial

- Details

- Hits: 9435

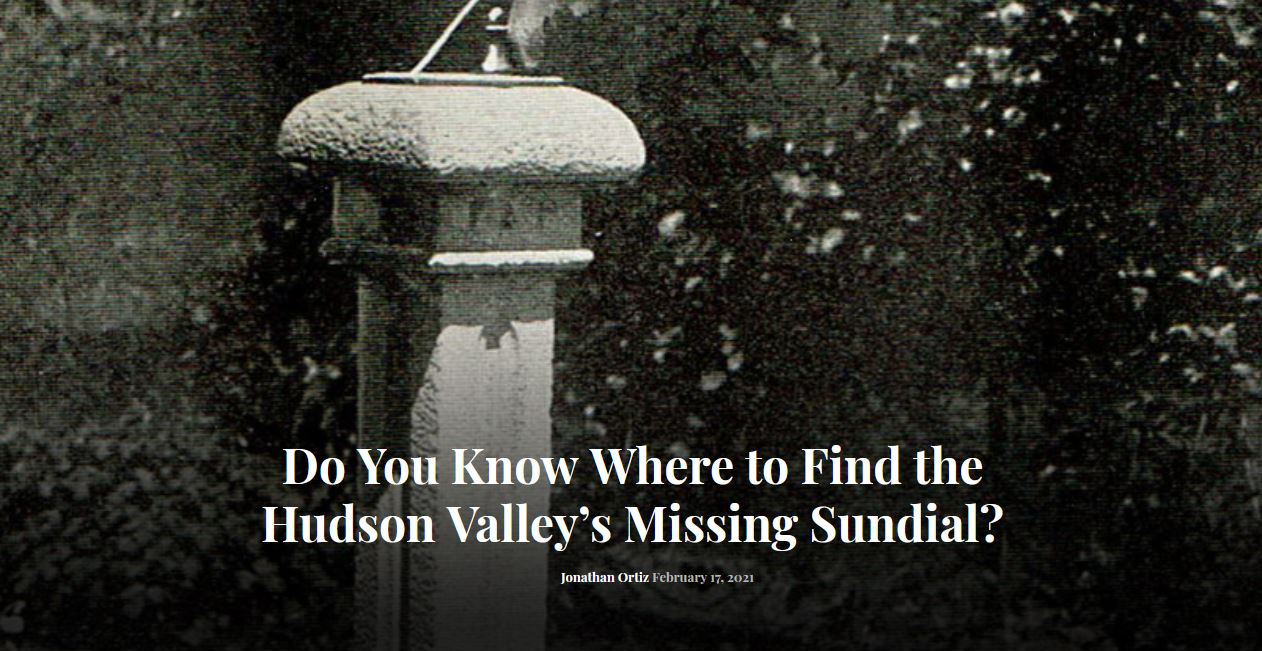

This article is reproduced by permission from Hudson Valley on-line magazine of Feb 17,2021 and can accessed directly at https://hvmag.com/life-style/history/missing-sundial-hudson-valley-hillside-dean-sage/ It was written by Jonathan Ortiz with information from NASS/BSS member Martin Jenkins and fellow researcher Kevin Franklin.

Menands’ village historian dives headfirst into the past to discover the whereabouts of a sundial that once resided at the Hillside estate in Albany County. There’s a mystery to solve in the Hudson Valley. It involves a cast of unlikely players: a local historian, a British society, a wealthy Albany County businessman, and a famed Scottish novelist.

|

|

The object of their attention? A missing sundial. Its last known whereabouts are the estate of Dean Sage, in Albany County’s village of Menands, which lies inside the Town of Colonie; however, this conundrum begins much, much farther away — in Scotland, to be exact.

“It’s a trans-Atlantic mystery,” says Kevin Franklin, Menands’ village historian and a former Menands police officer.

In 2020, Franklin was contacted by Martin and Janet Jenkins, two members of the British Sundial Society. They sought information about Hillside, the former Albany County estate of Dean Sage, son of Henry W. Sage of famed lumber firm H.W. Sage Co. fame. Hillside is located on the north side of the Menand Road (now State Rt. 378).

Interestingly enough, their purpose in finding this sundial makes the story ever more complicated. The device once located in Menands is actually a replica of another sundial from the Abbottsford estate of famed Scottish writer Sir Walter Scott. Now, there stands only a pedestal upon which the original sundial once sat.

“It is not known what the Scott sundial looked like,” writes Martin Jenkins in a letter to Franklin. “If the replica sundial made for Hillside could be traced, then a replacement replica could be made for Abbotsford in Scotland, the pillar then no longer standing silent and unadorned.”

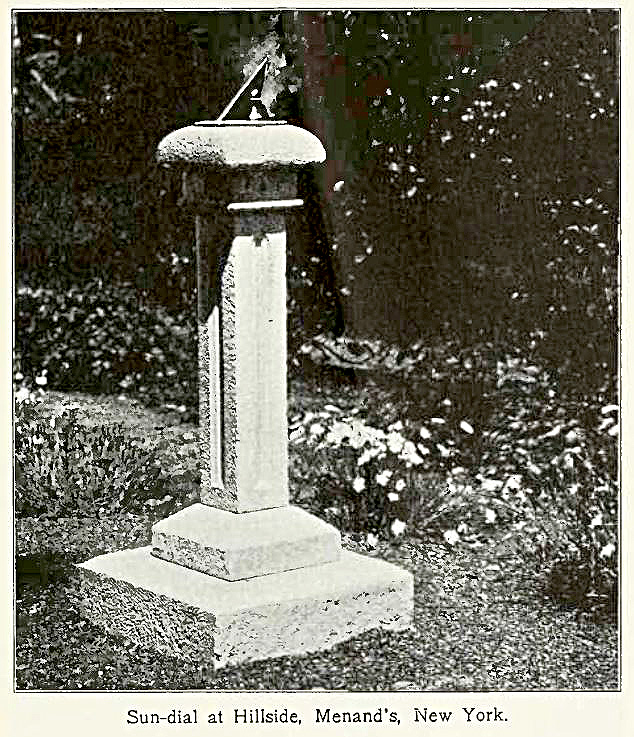

Several books make reference to both the original sundial and the replica. Most recently the March 2019 edition of the British Sundial Society Bulletin by Denis Cowan refers to the fact that a replica sundial was made for “Hillside, Menands, NY.” The 1902 edition of Sun-Dials and Roses of Yesterday by Alice Morse Earle shows the replica sundial to be in existence at Hillside, in the Shakespeare Garden border. In Ye Sundial Booke by T. Geoffrey W. Henslow in 1914, there are two sketches, one showing the sundial pillar at Abbotsford, Scotland, and the other depicting the replica sundial at Hillside.

Lastly, in The Book of Sun-Dials, the author Margaret Gatty apparently made her sketch of the sundial pillar at Abbotsford in 1839, but, by then, the sundial was missing — more than likely stolen.

Despite extensive documentation, many questions remain. What was the connection between Sir Walter Scott and Hillside? Who commissioned the Hillside replica? And, most importantly, what happened to the replica?

It was here that Franklin picked up the trail, starting with the local angle: Dean Sage.

“The Sages were immensely wealthy,” explains Franklin. “Their wealth evolved around the exporting of lumber from the Michigan area across the Erie Canal to the ‘Lumber District’ of Albany.”

Researching Sage’s background did reveal one important fact, and the potential connection between him and Scott: Sage was both a bibliophile and an avid fisherman.

|

Replica of Sir Walter’s Sundial | Photo by Alice Morse Earle, public domain |

He wrote the famous fly fishing book Ristigouche and Its Salmon Fishing in 1888. It was published by David Douglas of Edinburgh, whose name also appears in Sun-Dials and Roses of Yesterday. There, it is stated that Sage’s replica sundial was, “commissioned by the publisher Douglas.”

Douglas has another publisher’s credit — in The Journal of Sir Walter Scott. Scott kept a daily journal from 1827 until his death in 1832. These journals were published in 1890 by the very same Douglas who published for Sage.

While Sage, born in 1841, could never have met Scott, who died in 1832, it is well known that Abbotsford is on the banks of the River Tweed and has been famous for salmon fishing since Roman times. The Tweed Commissioners whose responsibility it was to manage the river and its fish was set up by Scott in 1805. It seems likely that Dean Sage visited Abbotsford at some time as part of his salmon fishing interest.

“It would not be beyond the realm of imagination for Dean Sage to have gotten either a sketch or drawing, maybe even a photograph, of this sundial at least the base that still remains at the Abbottsford and had that duplicated,” explains Franklin.

The final question remains: Where is the Hillside sundial?

Mr. Franklin continues to follow up with past residents of the area and any leads which would help locate the missing sundial of Hillside.

Have any info on the missing Hillside sundial? Send any information or clues to this local mystery to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., or directly to Kevin Franklin at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

[You may also send any information to the North American Sundial Society, at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. ]

- Details

- Hits: 15758

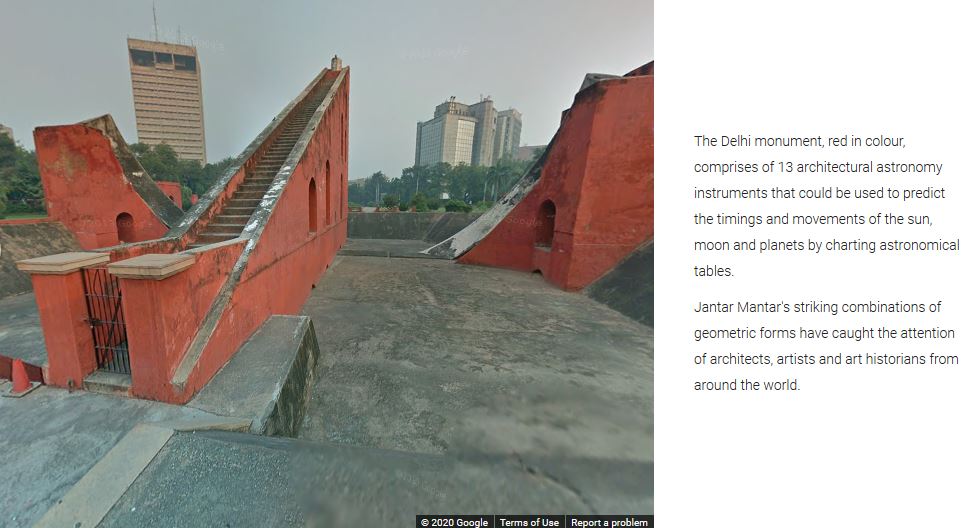

Google Arts and Culture offers you to take a virtual tour of the 13th century observatory Jantar Mantar in Delhi. At the opening view (see the website link below), the Google tour explains: "Innovations in architectural astronomy: The Jantar Mantar Obervatory, Delhi's outdoor astronomical observatory is the earliest of five observatories built by Sawai Jai Singh II across India. It is dominated by a huge sundial and houses other innovative instruments that help plot the course of heavenly bodies...."

Google Arts and Culture offers you to take a virtual tour of the 13th century observatory Jantar Mantar in Delhi. At the opening view (see the website link below), the Google tour explains: "Innovations in architectural astronomy: The Jantar Mantar Obervatory, Delhi's outdoor astronomical observatory is the earliest of five observatories built by Sawai Jai Singh II across India. It is dominated by a huge sundial and houses other innovative instruments that help plot the course of heavenly bodies...."

"The Maharaja designed four similar observatories in Jaipur, Ujjain, Mathura and Varanasi to help and improve upon the studies of space and time. The Jantar Mantar in Jaipur is now the largest among them." Google gives us a glipse of the large equatorial dial of the Man Singh Observatory in Varanasi and then focuses on the four large brick and plaster instruments at Jantar Mantar: the Ram yantra, two circular structures next to each other used to observe celestial objects; the Samrat yantra, one of the largest equatorial dials in the world with stairs leading to the top of the triangular gnomon (looking like stairs to the heavens) and surrounded by a large equatorial band to measure solar time; the Jai Prakash yantra that consist of two elaborate sunken hemispheres so large that there are stairs from the bottom leading between huge longitudinal bands; and the Misra yantra, which is shaped like a heart and is composed of five different sun and alignment instruments to determine the shortest and longest days of the year at the solstices.

Take a personal visit to these historic astronomical and solar instruments at: The Jantar Mantar Observatory - Google Arts & Culture

- Details

- Hits: 13733

From the Harvard Gazette - Dec 9, 2019 : "Since 1672 Harvard University has been acquiring scientific instruments for teaching and research. In 1948 the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments was established...[and has] grown to more than 20,000 objects making it one of the three largest university collections of its kind in the world"

From the Harvard Gazette - Dec 9, 2019 : "Since 1672 Harvard University has been acquiring scientific instruments for teaching and research. In 1948 the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments was established...[and has] grown to more than 20,000 objects making it one of the three largest university collections of its kind in the world"

As an illustration of the collection is a photograph of ivory pocket sundials shown here, made in Nuremberg, Germany between 1575 and 1645. These elegant diptych sundials represented the 16th and 17th century equivalent of pocket watches, especially for wealthy traveling merchants to keep track of time. "Harvard has the largest collection of sundials in North America, a gift of David P. Wheatland, Class of 1922."

As described by Dr. Sara Schechner in Time of Our Lives - Sundials of the Adler Planetarium who is the David P. Wheatland Curator of Historical Instruments at Harvard describes the diptych as "fashioned from ivory, gilt brass, carved wood, and wood covered by printed paper. The materials offer hints on the social status of their owners. So too do common and novel accessories found on the instruments. A directory of cities and their latitudes suggests an owner who traveled... The association is stronger when the diptych combines a gazetteer with particular sundials that found the time according to the sundry conventions of England, France, Germany, and Italy. A merchant crossing a border would have needed to know how to set up an appointment with his clients. How many hours would there be to transact business or to journey along the road? Calendrical devices on the diptych showed him the length of the day and night throughout the year...[and] the diptych's lunar volvelle gave ...the moon's phase. It also assisted the owner in finding the time by moonlight...[And] a diptych with a magnetic compass [allowed proper and immediate orienting the sundial]."

Read more at: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/12/collection-of-historical-scientific-instruments-continues-to-amaze/

Sun-Dials and Roses of Yesterday / Wikimedia Commons

Sun-Dials and Roses of Yesterday / Wikimedia Commons